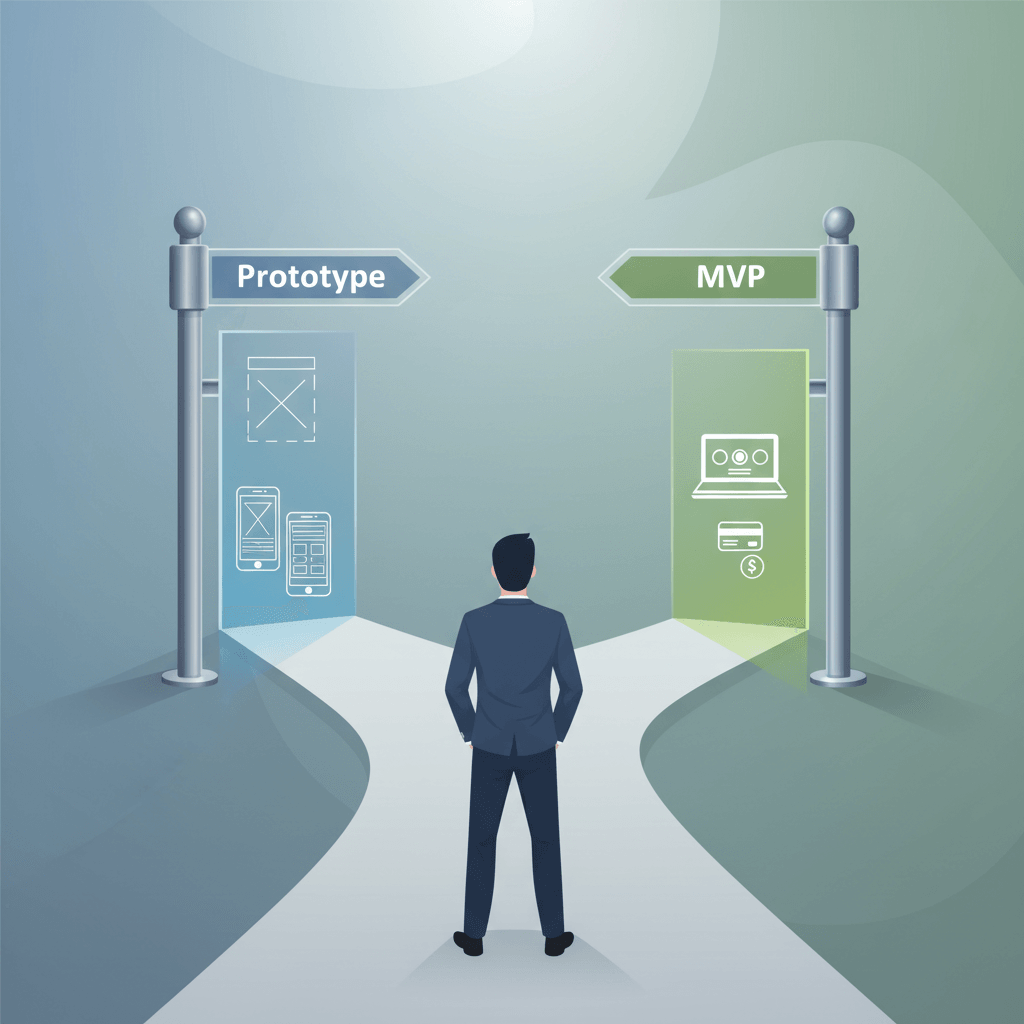

You have a product idea you cannot stop thinking about. Now you are stuck at the first fork in the road: MVP vs Prototype.

People throw both terms around like they mean the same thing. They do not. If you pick the wrong starting point, you can waste months and burn through your budget before you learn anything real.

Here is the simple difference. A prototype tests usability, meaning “Can people understand and use this?” An MVP tests viability, meaning “Will people adopt this, and will they pay?”

The first decision that saves you time and money

This is not a technical choice. It is a strategy choice.

Many startups fail because they build something no one truly wants. You can get positive feedback on a great-looking demo and still fail in the market. That usually happens when founders treat design feedback like market proof.

This guide breaks down when to start with a prototype, when to start with an MVP, and how to avoid confusing the two.

Key takeaway: A prototype is a test of the experience. An MVP is a test of the business. They answer different questions at different moments.

Quick comparison: prototype vs MVP

Use this table to get oriented, then we will go deeper.

| Attribute | Prototype | MVP (Minimum Viable Product) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Validate design and user flow | Validate the core business idea |

| Audience | Team, investors, early test users | Real early-adopter customers |

| Functionality | Mostly visual, interactive but not fully functional | Working product with limited features |

| Effort and cost | Low (weeks, ~ $5k–$10k) | Higher (months, ~ $30k–$50k+) |

A prototype gets feedback in a meeting room. An MVP gets feedback from the market. That is the difference that matters.

What a prototype is really for

A prototype is a visual model of your product. Think of it like a movie set. It looks real from the front, but there is little or nothing working behind the scenes.

Its job is to answer one question: “Can people figure this out without help?”

This is why prototypes are perfect for testing user flows like onboarding, checkout, or a dashboard layout. You learn what confuses people before you spend money on engineering.

What a prototype can look like

Prototypes range from simple sketches to realistic clickable screens. You do not need to be a designer to start.

- Paper sketches: Draw screens and map the steps. This is fast and costs almost nothing.

- Wireframes: Simple digital layouts that show structure, not brand style.

- Interactive mockups: Clickable, high-fidelity screens built in tools like Figma.

The advantage is speed. You can change a design in minutes. Changing real code takes far longer.

Why founders should like prototypes

A prototype is built to be edited, argued about, and even thrown away. That is a feature, not a flaw.

It helps you test assumptions about how the product should feel and flow. You do that before you lock yourself into expensive development work.

A prototype should fail fast and cheap. It is there to protect your build phase from avoidable UX mistakes.

This is also why prototypes work well in a structured strategy phase. You can align your team, get clear feedback, and reduce rework later.

What a minimum viable product is

An MVP is the first working version of your product. It is not a mockup. It is real software that real users can access.

Its purpose is simple. It tests whether your product delivers enough value that people will take action. That action can be signing up, returning, and ideally paying.

What “viable” means in practice

“Viable” means it works well enough to solve a real problem for a specific group of early adopters.

It does not mean “perfect.” It does not mean “feature complete.” It means the core value is there, and the product is stable enough to learn from.

“Minimum” is where founders struggle. Many people try to build a smaller version of the full dream product. That still costs too much, and it delays learning.

A prototype asks, “Is this experience clear?” An MVP asks, “Is this worth doing, and will anyone pay for it?”

A well-known example is Dropbox. Early on, they validated demand with a short demo video that explained the core value. It helped them confirm interest before heavy infrastructure work.

The goal is learning, not revenue

Your MVP can make money, but that is not the main point. The point is learning quickly with real behavior data.

You learn what people do, not just what they say they will do. You see how they use the product, where they drop off, what they pay for, and what they ignore.

This is also why MVP work reduces risk. Instead of spending six months building a full product that might miss the mark, you build a smaller working version and test the core assumptions first.

If you want a step-by-step playbook, see our MVP development guide for founders. It covers scoping, planning, and launch basics.

A practical comparison founders can use

When founders talk through this decision, the same topics come up every time. What is it for? How long does it take? How much does it cost? What risk does it remove?

Use the sections below to match the build type to your biggest unknown.

Purpose and goals

A prototype is for usability questions.

- Is the interface intuitive?

- Do users know what to do next?

- Is the flow clear from start to finish?

An MVP is for market and business questions.

- Is the problem painful enough that people search for a solution?

- Will a real segment adopt it?

- Will they pay, and does pricing make sense?

A prototype tests how someone might interact with the idea. An MVP tests if they will adopt it in real life.

Time and cost differences

A good interactive prototype is usually a focused effort. Many teams can create it in 2 to 4 weeks. Budget is often around $5,000 to $10,000, since you are paying for UX and design work, not engineering.

A true MVP is a larger build because it is real software. Typical timelines are 8 to 12 weeks, sometimes more. Budgets often start around $30,000 to $50,000+, depending on complexity, integrations, security, and platform needs.

If you are a non-technical founder, this gap matters. You can answer usability questions for a fraction of the cost, before you commit to development.

Side-by-side: what you get

This table is built to help you pick your next step based on what you need to validate now.

| Criteria | Prototype (focus on “how”) | MVP (focus on “if”) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Validate the user experience (UX) and interface (UI) | Validate market demand and the business hypothesis |

| Key question | “Is this intuitive and easy to use?” | “Will people use it and pay for it?” |

| Functionality | No real backend, usually a clickable mockup | Real functionality, limited to the core feature |

| Deliverable | Clickable design file (often in Figma) | Live app used by early adopters |

| Timeline | 2–4 weeks | 8–12+ weeks |

| Estimated cost | $5,000–$10,000 | $30,000–$50,000+ |

| Risk reduced | Usability risk: You avoid building a confusing experience. | Market risk: You avoid building a product no one wants. |

Risk: what each one protects you from

A prototype reduces design and usability risk. It helps you spot confusion early, when changes are cheap.

An MVP reduces market and business risk. It tests real demand, real usage, and real buying behavior.

An MVP also starts to reduce technical risk. It is your first proof that your chosen tech can deliver the core value reliably.

How to choose your starting point

This choice gets simpler when you name your biggest uncertainty.

Are you unsure about how the product should work and feel? Or are you unsure anyone will want it enough to pay? Your answer points to the right first step.

When to start with a prototype

Start with a prototype when the unknowns are inside the product experience. You are still deciding what the flow should be and what screens matter.

A prototype is often the right first move if:

- You have a complex user journey. Multi-step onboarding, detailed checkout, or advanced dashboards are hard to get right on the first try.

- You need alignment with stakeholders. A clickable mockup makes the idea concrete, so feedback becomes specific.

- You want to compare designs. Testing two layouts in a mockup is far cheaper than building both.

A prototype is for validating clarity. It helps you ask, “Does this make sense?” before you pay for development.

When to start with an MVP

Start with an MVP when your core idea feels stable, but demand is still a guess. At this point, the unknown is outside the product.

An MVP is usually the right first move if:

- You have a clear problem and audience. You have talked to potential users and can describe the pain in detail.

- You are ready to test real adoption. You want to see sign-ups, usage, retention, and payment.

- You need behavior data. You are done relying on opinions and want real evidence.

If you are still refining the “how,” build the prototype first. If you are confident in the “how” and need to test the “if,” build the MVP.

A simple example from client work

A client came to us with an idea for an online education platform for financial analysts. The user journey was detailed. It included course modules, resource libraries, and progress tracking.

We started with a prototype. We tested the clickable flow with five analysts. Within days, we found friction in navigation and content structure, and we fixed it in design.

Then we built the MVP. It did not include all planned courses. It included one complete course, a basic dashboard, and a working payment flow.

The question was focused: would busy analysts pay $299 for this course? The MVP proved they would, which funded the next build phase.

If you are choosing a tech approach for your own build, see these popular tech stack examples.

Your next steps: turn the decision into a plan

Clarity is only useful if it leads to action. Below are two simple checklists. Pick the one that matches your decision and complete it before you spend money.

If you chose a prototype

Your goal is to remove UX risk before development starts. Keep your scope tight and focus on the main path.

-

Define the core user flow: Choose one path a user must complete, step by step. Examples include “sign up and create a project” or “search and complete checkout.”

-

Write your top 3 to 5 questions: Make them specific. For example, “Do users understand the pricing choice?” or “Can users find the next lesson without help?”

If you chose an MVP

Your goal is to test your business assumptions with real users. That means focus and restraint.

-

Cut to the minimum feature set: List every feature you want, then remove anything not required to deliver the core value the first time.

-

Define your first ten users: Name the exact type of person or company. Your first release is for them, not everyone.

-

Pick one success metric: Choose a single measurable target, like 10 paying customers, a 20% conversion rate, or a retention goal. Make it clear what “proof” looks like.

Mixing these stages is expensive. Design praise does not equal market proof. The point of this process is to get the right evidence at the right time.

This is the kind of early planning we focus on with founders. The goal is simple: build the right thing before you commit to code.

Once you have your scope, the next question is budget. This guide helps you estimate it: guide to MVP development costs.

Frequently asked questions

These are the questions founders ask most when they are deciding what to build first.

Can I skip the prototype and go straight to an MVP?

Yes, but it is a risk if your product has a complex flow. You can end up building real software, then learn users cannot figure it out.

In many cases, spending a few weeks on a clickable prototype saves weeks of redesign and rebuild work later.

How do I know if my MVP is “minimum” enough?

Use one test: can the first user get the core value without this feature?

If the answer is yes, remove it from the MVP. Save it for a later release when you have proof of demand.

- List every feature idea.

- For each one, ask if the core value still works without it.

- Cut everything that is not required for the first successful use case.

What if my MVP does not get traction?

That is not a dead end. It is data.

Talk to the people who signed up, and especially the ones who did not convert. Look for patterns around urgency, pricing, trust, and friction in the flow.

An MVP that does not take off can still be a win if it saves you from building the wrong product at full scale.

Conclusion: pick the test you need most

If you need to prove the experience is clear, start with a prototype. If you need to prove the market wants it, start with an MVP.

If you want a partner to help you scope, plan, and build with focus, visit Refact and start the conversation.