You want to build a product, move fast, and prove your idea. But you cannot code, and hiring technical help feels like a black box. If you are trying to hire developers for startup work, you are not alone, and you are not behind.

This guide is for non-technical founders who need a clear plan. You will learn what to hire first, which hiring path fits your stage, and how to vet talent without pretending to be an engineer.

Why hiring feels so hard right now

If it feels like every good engineer is either overpriced or already taken, that is a real problem in the market. Many founders are competing for the same small group of experienced people.

Several trends stack up at once. AI-related roles pull senior talent away from general product work. Many experienced engineers are also leaving full-time roles or retiring. On top of that, global hiring has more friction than it did a few years ago.

A quick look at the numbers

Depending on the source, estimates vary, but the pattern is consistent. Demand for senior engineers is high, and supply is tight. Many senior candidates field multiple offers before they seriously interview.

This is not meant to scare you. It is meant to help you plan. The goal is not to win a salary war. The goal is to make smart hiring choices that fit your stage and budget.

What this means for early-stage startups

Here are the most common problems founders run into, plus what to do about them.

| Challenge | Impact on startups | What this means for you |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy competition | Large companies and well-funded startups can offer higher cash and stronger brand pull. | Compete on mission, ownership, autonomy, and speed of impact. |

| Higher compensation | Experienced engineers cost more than most first-time founders expect. | Define the role tightly so you do not over-hire or hire the wrong profile. |

| Fewer “plug-in” seniors | True senior engineers who can lead product, architecture, and delivery are scarce. | Consider a different model (fractional, studio, or a senior lead with a smaller build scope). |

The old playbook of posting a job and waiting is weaker than it used to be. Your advantage is focus. When you are clear on what you need next, you can attract the right person faster.

Define what you actually need before you hire

Before you write a job post, stop and get specific. Most expensive hiring mistakes come from unclear scope.

Many founders default to “full-stack developer” because it sounds safe. But “full-stack” can mean ten different things. The better question is simple: what must be true in 90 days for your startup to be in a better place?

Are you trying to confirm the problem is real? Are you trying to validate a solution with users? Or are you ready to build and ship an MVP?

A quick story: the founder who hired too soon

A founder I met was determined to hire a senior engineer to build a complex platform. He spent weeks searching and paid a high salary when he finally found someone.

Then progress stalled. The engineer kept asking for wireframes, user flows, and edge cases. The founder felt the engineer “didn’t get it.” The engineer felt they were being asked to build without a clear plan.

The real issue was timing. The company did not need a senior engineer yet. It needed product and design clarity first. The founder later hired a freelance designer, got a prototype and flows in a few weeks, and only then restarted engineering with a clearer scope.

Clarity before code is non-negotiable. If you are not sure what to build, the best developer in the world cannot guess it for you.

Which stage are you in?

Most early-stage work fits into one of three stages. Your stage should decide who you hire first.

-

Strategy stage: You have an idea, but the MVP is still fuzzy. You are unsure which user problem matters most, what the core workflow is, or how you will charge. Your first hire may be product strategy support, not engineering.

-

Design stage: You know the problem and the MVP scope, but you need flows, wireframes, and a clickable prototype. Your fastest path is often a strong UI/UX designer, not a developer.

-

Build stage: You have a validated concept, a defined MVP, and clear acceptance criteria. Now it makes sense to bring in engineering to ship a first version.

If you want a simple way to document this, write a lightweight requirements doc. Start with user goals, the main screens, and “done means” for each feature. This guide can help you structure it: product requirements document template.

This step is not bureaucracy. It is the fastest way to avoid mis-hires, rework, and burnout.

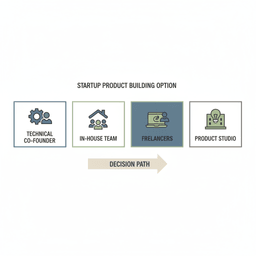

The four paths to building your product

Once you know what you need next, you have to choose how to get it built. Most founders jump straight to a full-time hire, but that is only one option.

Below are the four most common models, with clear trade-offs in speed, cost, and risk.

1) Find a technical co-founder

This can be a great match when you are pre-seed and still shaping the product. A technical co-founder is not just writing code. They help choose the approach, set quality standards, and make product trade-offs with you.

The cost is usually equity, not cash. That also makes this the biggest commitment you can make. In many cases, this means giving up 25% to 50% ownership, depending on stage and who brings what.

The biggest risk is mismatch. If you do not align on pace, product taste, and goals, it can derail the company. Treat this like a long-term partnership, because it is.

2) Hire in-house employees

In-house engineers give you focus and ownership. Their time is dedicated to your product, and the learning stays inside the company.

The downside is cost and overhead. Beyond salary, you pay for taxes, benefits, equipment, and management time. You also need enough stable work to keep a full-time person productive.

This model often makes the most sense after you have traction and a roadmap you believe in.

3) Use freelance contractors

Freelancers are great for well-defined tasks. Examples include building a landing page, adding a payment screen, or fixing a specific bug list.

The risk is fragmentation. If you rotate through multiple freelancers, knowledge gets stuck in different heads, and the code can become inconsistent. Freelancers also tend to execute what you ask for, not challenge the plan.

If you go this route, keep the scope small and the expectations very clear.

4) Partner with an agency or product studio

A studio gives you a ready team. You can get product thinking, design, and engineering without building a full department on day one.

This can work well if you need help turning a concept into an MVP and shipping it fast with fewer surprises. It can also reduce founder load, since you are not trying to manage every technical detail yourself.

The main trade-off is cost, since you are paying for a team and a process. For many founders, the real comparison is not “studio vs freelancer.” It is “studio cost vs the cost of months of wrong work.”

Hiring model comparison

| Model | Best for | Typical cost | Risk level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical co-founder | Idea stage, long-term build partner needed | Low cash, high equity (often 25% to 50%) | High |

| In-house employees | Post-traction, clear roadmap, steady work | High (salary + overhead) | Medium to high |

| Freelancers | Small, defined tasks | Medium (hourly or fixed bid) | Medium |

| Agency or studio | Need a team and product support, fast MVP delivery | High (retainer or project) | Lower |

Action step: Decide what you can commit for the next six months: cash, your time to manage the work, and how much risk you can take. Then choose the model that fits that reality.

If you are in the build stage and want to understand common tech choices, these popular tech stack examples can help you ask better questions during interviews.

How to vet technical talent when you cannot code

This is where many founders freeze. You worry you will get fooled, or you will hire someone who can talk but cannot ship.

Good news: you do not need to judge code line by line. Your job is to judge outcomes, thinking, and communication. Those traits predict success in early-stage work.

What to look for in a portfolio (without reading code)

When a candidate shares GitHub, a website, or case studies, focus on signals you can verify.

-

Clear documentation: Are there README files that explain what the project does and how to run it? Clear writing usually means clear thinking.

-

Shipped work: Are there live links to working apps? Shipping beats “almost done.”

-

Specific contribution: On team projects, can they explain what they owned? Look for “I built X” and “I decided Y because…”

You are not a code reviewer. You are looking for professionalism, follow-through, and proof they can finish work.

The best interview question for non-technical founders

Skip puzzle questions and trivia. Use a prompt that forces real explanation.

Pick one portfolio project and ask:

“Walk me through a hard technical decision you made on this project. I am not a developer, so explain it like you would to a business partner. What was the problem, what options did you consider, and why did you choose the final approach?”

Listen for three things:

-

Clarity: They can explain trade-offs in plain language, without talking down to you.

-

Judgment: They considered time, cost, reliability, and future maintenance, not just what was “cool.”

-

Ownership: They can name a decision they made and the impact it had.

If they get defensive, vague, or blame others, that is a warning sign.

Use a paid test project that looks like real work

Once you have a top candidate, run a small paid test. Keep it short and realistic. Avoid generic algorithm tasks that do not reflect product work.

Bad test: “Reverse a binary tree.”

Good test: “Add a contact form to this page. Collect name and email. Send the submission to this address. Spend no more than 3 to 4 hours. Write down your steps and assumptions.”

This shows how they:

-

Ask questions when requirements are unclear

-

Communicate progress

-

Deliver a complete, working result

Action step: Write a one-page interview plan. Include three portfolio questions, the decision prompt above, and one paid test idea tied to your MVP.

Make the offer and set up the first 90 days

Hiring does not end when someone says yes. Your offer and onboarding shape how fast they ramp and how much trust you build.

For early-stage startups, the offer is usually a trade between cash and ownership. You may not match big-company pay. That is fine, as long as you are honest and you offer real upside.

How to handle the salary vs equity conversation

Benchmarks vary by location, seniority, and market timing. For a first or second engineering hire at pre-seed or seed, founders often offer a salary below big-company rates, plus equity.

For early hires, equity grants commonly land in a wide band, such as 0.5% to 2% vesting over four years. Your numbers should reflect role impact, risk, and how close you are to revenue.

Be clear about what the equity means. Share basics like vesting schedule, cliff, and how many total shares exist so they can understand the percentage.

The goal is not to “get a bargain.” The goal is to build a fair package that makes the person feel like an owner, not a short-term contractor.

A simple onboarding plan that works

You do not need a complex onboarding system. You need three things: context, cadence, and a first win.

-

Context: Spend a few hours on the product story. Who is the user, what pain are you fixing, and what does success look like in 12 months?

-

Cadence: Set a weekly check-in and decide how you communicate day to day. Keep it consistent.

-

First win: Set a clear 30-day goal. Pick something meaningful but not huge, like shipping one small feature, improving onboarding, or fixing a known set of bugs.

If you are still unsure about budget, start with a cost range before you hire. This guide helps founders estimate spend and avoid surprises: software development cost estimation guide.

Action step: Before day one, write a one-page onboarding doc. Include the 30-day goal, meeting rhythm, and links to key product notes.

Common hiring mistakes founders make

Most problems come from the same root cause: unclear expectations. The founder thinks they are buying an MVP. The developer thinks they are building a scalable platform.

That mismatch creates slow progress, tense meetings, and wasted money.

Mistake 1: hiring out of urgency

When you feel behind, it is tempting to hire the first person who seems “good enough.” Skipping a paid test or reference checks feels faster.

In reality, a rushed hire often costs months. If you later need to replace them, you lose time, money, and momentum.

Mistake 2: waiting for the “perfect” hire

The opposite trap is endless searching. You interview for weeks, build spreadsheets, and keep thinking the next candidate will be perfect.

Meanwhile, you ship nothing and learn nothing from users. Aim for a solid hire with a clear first project, then improve from there.

Mistake 3: vague scope and moving targets

If the developer hears “build the app,” they will fill in missing details with their own assumptions. That is not their fault. It is a scope problem.

Fix this by writing “What we are building next.” Keep it to one page. List the three most important outcomes for the next 90 days, plus what “done” means.

Strong hiring is not magic. It is clear scope, consistent communication, and a realistic plan for the next quarter.

FAQs from non-technical founders

How much should I budget for my first developer?

It depends on location and seniority. In the US, a solid mid-level developer often costs six figures, plus equity. Contractors can range widely by skill and specialty.

The best way to think about cost is value per month, not hourly price. A stronger engineer can ship faster, avoid dead ends, and reduce rework.

What is the difference between a freelancer and a product studio?

A freelancer is usually a single person hired for a task you already defined. It works best when the scope is clear and the work is limited.

A product studio is closer to a team-for-hire. You get product thinking, design, and engineering working together. This can be helpful when you need guidance on what to build and how to ship it.

Should I give equity to my first engineering hire?

In many early-stage startups, yes. Equity helps you compete when cash is limited, and it signals partnership.

Use standard vesting terms, explain the upside and the risk, and put everything in writing. If someone is uncomfortable with any equity conversation, that is useful signal too.

Conclusion: make the next hire a focused bet

If you take one idea from this article, make it this: do not hire “a developer.” Hire for a specific 90-day outcome.

Get clear on your stage, pick the right build model, and vet for communication and judgment, not just buzzwords. That is how non-technical founders build products that ship.

At Refact, we work as a dedicated product team for founders, blending strategy, design, and development to ship real products. If you want help defining scope and building your MVP, you can learn more about our approach.